Matt Hudak, AAMS®, CFP®

We don’t publicly engage in much discourse that touches the political spectrum. We believe the polarization of American society is the greatest geopolitical and economic risk we face today and in order to overcome this risk we need to come together. In turn, we do our best to put our energy into listening to a diverse range of ideas and opinions. Most of our personal ideology is centered around loving people who are different than us and coming together. At times, it can be difficult to publish about important economic topics and concepts without crossing lines into politics and divisive rhetoric. Nevertheless, we will attempt to take a neutral political perspective while addressing the challenges to the strength of our economy.

There are several key concepts we feel should be relatively apolitical and have benefits for both sides of the spectrum. These concepts are primarily monetary & economic—politics-adjacent, but overshadowed by divisive rhetoric and ineffective dialogue. Before we can engage any productive solution, of course, our political leaders must learn to work together. This collaboration seems nearly impossible, but it begins with each of us.

Money Supply, excessive government spending & debt, slowing GDP growth.

While a lot of the headline economic reports look good, and the 7 companies that represent the “stock market” have shot up (a little sarcasm for you. Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Meta, and Alphabet represent 31% of the S&P 500, what people mistakenly call the “stock market”). The reality of our economic environment is a little more complicated. We believe that we are currently in a ghost recession. Primarily because savings are low, people are feeling the pressure of higher costs and are thinking about how they use their money carefully. When we see positive data points, there are often divergent stories in the components it represents.

Before we suggest a few helpful ideas, we should identify the drivers behind the challenges facing our economy.

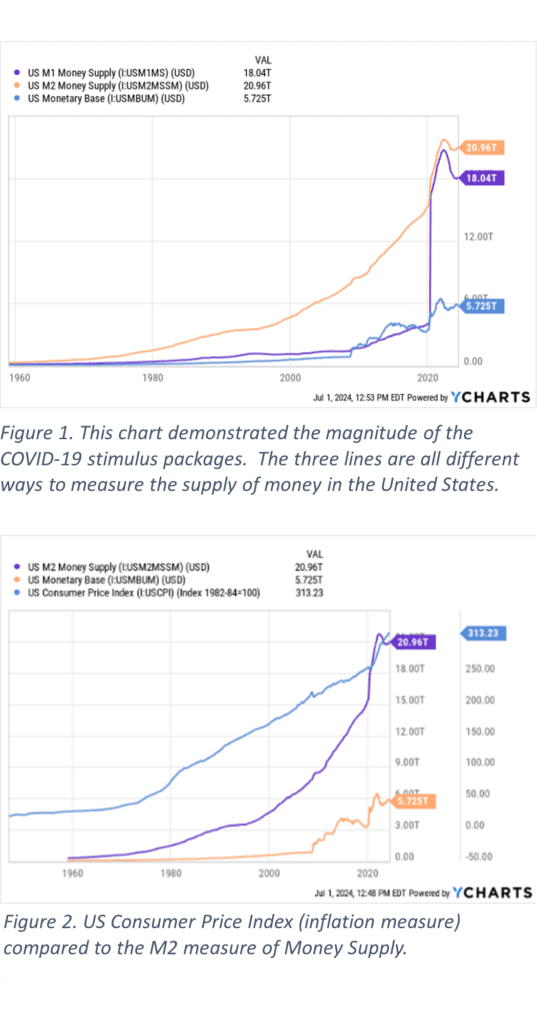

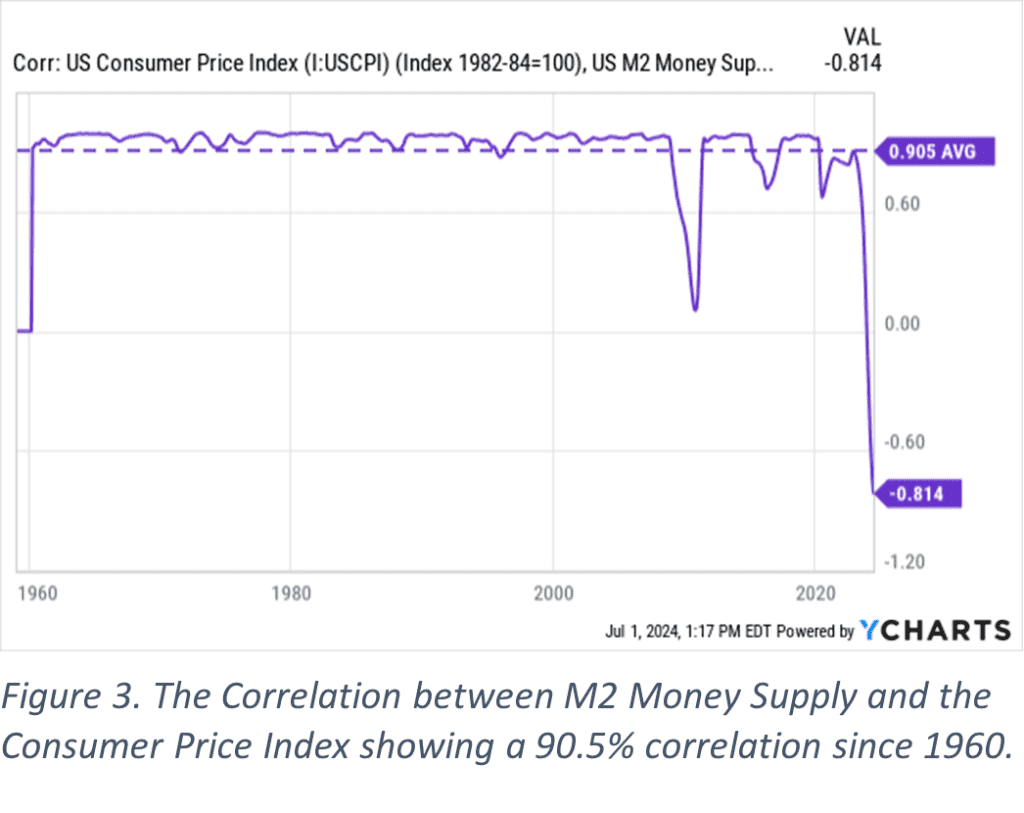

M2. If you’re an economics nerd, that’s all I should need to say. Most economists and officials are too busy trying to figure out how to turn on their flashlight to realize it’s high noon on a sunny day. Contrary to what you may perceive from the world’s obsession with central banks, inflation doesn’t have anything to do with interest rates. Interest rates can affect the speed of inflation, spreading it out over a slightly longer period of time, but no change in interest rate policy by the federal reserve can ultimately change the purchasing power of a dollar. What’s astonishing is that the obvious realities about the monetary system haven’t really been a part of the conversation at the policy level. Perhaps its because both parties are equally responsible for directly causing the current inflationary environment by more than tripling our money supply (M1) in less than 12 months. The M2 measure increased by 40% in the same timeframe (We think M2 will prove to be the predictor of inflation. To wit, prices and incomes will eventually reestablish balance with M2).

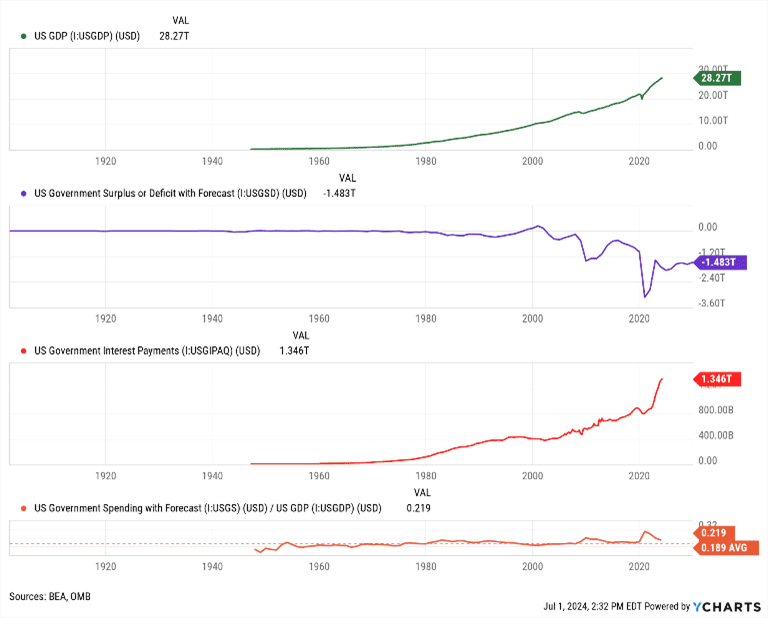

It shouldn’t go unnoticed that the M2 measure of money supply and inflation have a near perfect correlation and as seen in the chart in figure 3, until November of 2023, had never before been inverse. They move together 90.5% of the time. In fact, all of the anomalies shown in the chart are at point of major government intervention in the monetary system, and they are all followed by a rapid reversion to the normal correlation. We believe we will see the same effect in the present.

Simply put, inflation is the effect of supply and demand for the dollar. Just like the price of a carton of eggs or a used car changes depending on whether they are hard to find on a shelf or if the dealer can’t seem to move them off the lot, the dollar has more or less purchasing power if there is an abundant supply or if is scarcer in relation to goods and consumers. Policies that are effective at combating the inflationary riptide of a surging money supply will either claw back such supply, limit its future growth or distribute it among a higher number of productive citizens.

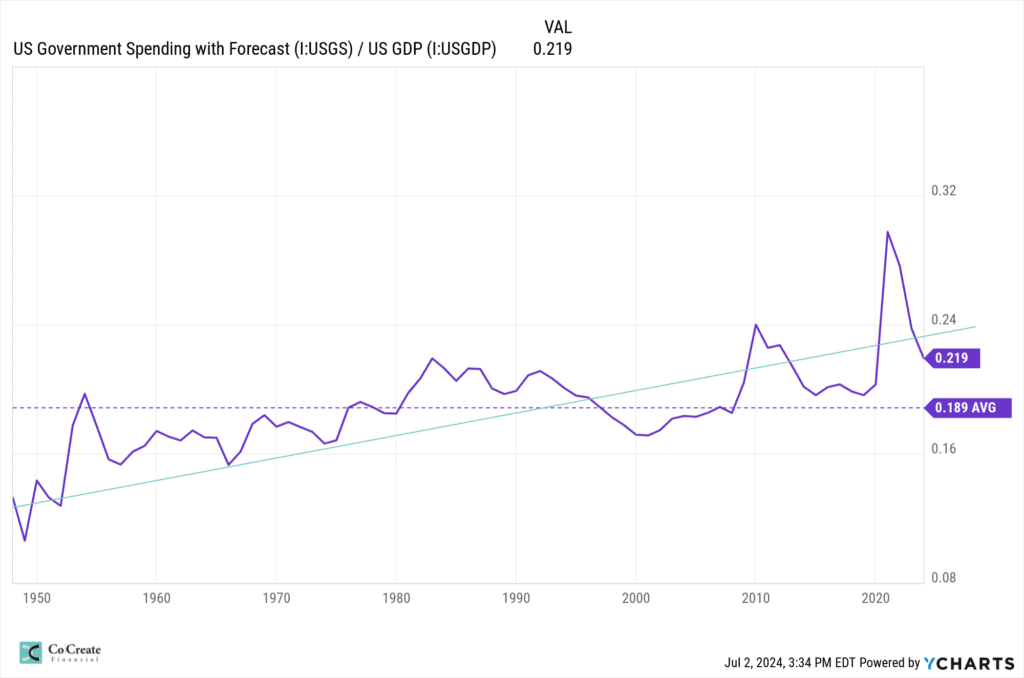

Government spending as a percentage of GDP isn’t as much through the roof as it might seem when we compare it to historical norms, but it's too high for a healthy and growing economy. This is especially true with the current level of debt. Republicans and Democrats alike stand on platforms to expand spending. Regardless of what each of us deems worthy of government funding, those funds need to be in balance with the overall productivity of our country. GDP is the total value of goods and services the US produces (consumer spending, government spending, investment, and net exports). If we imagine a scenario in which Government spending accounted for 100% of GDP, where would they get their revenue? In this hyperbole, there are no businesses or personal revenues to tax (taxable revenues begin with business investment and consumers spending on their product)

The key in a realistic solution is in finding a balance between government spending and non-government productivity. I would suggest that a healthy level of government spending (in the system we have in place today) should not exceed the 18% average (since 1947), but is probably better averaging 14%-15%. If it exceeds that rate, any additional revenue it needs has to come from non-tax policy that stimulates productivity growth in the non-government components of GDP.

Here are 5 things we believe could help to fix a broken economy.

1. Expand and expedite LEGAL immigration

This is not a “border wall conversation,” and it is a particularly difficult conversation to have given the contention surrounding the topic of illegal immigration.

The process for allowing a person who lawfully applies to leave their country to enter the United States, is painfully slow—bureaucracy for the bureaucracy’s sake. It would be easy to expedite this process for productive, low-risk people who want to come to the US to work, pay taxes and spend money. The median processing time of an application for an immediate family member of a US citizen is 11.3 months and an application for an alien entrepreneur (I-526) is 53 months. A green card takes 13.6 months. Half these applications take longer and are probably just sitting on a desk.[1]

Immigration is inherently disinflationary. When we discuss inflation in functional terms, it really must be done hand in hand with population growth. Inflation and disinflation are the impact of supply imbalance between the dollars available in the system and the goods & services available. The goods and services are, at least in our present circumstances, relatively static (except, of course, when supply chains are temporarily disrupted). Because those are static, more money means higher prices. They are directly correlated as we discussed above. Adding more people into the equation, however, dilutes the money supply. Ultimately as the end consumer, we choose where we direct the funds we possess. If I don’t have as many dollars, I am more careful about how I spend them. I’m also more inclined to be more productive so that I can earn more.

GDP growth in the US is negatively impacted by a less productive population. This is both due to an aging population (i.e. retiring baby boomers and increasing life expectancy) and an economy that is highly developed. Immigrants have proven to be highly productive and innovative because they are motivated by the opportunities of their new situation. Immigrants also tend to be younger and have larger families than those born in the US. By expediting the application process for entry into the United States, we can effectively boost GDP Growth while curbing inflation.

2. Re-privatize home financing and student loan programs

Imagine you’re selling your home and you have two buyers. Both of the buyers can afford to pay $7,000 toward their monthly mortgage payment and have saved $40,000 for a down payment. The first buyer has a bank that will lend 80% of the purchase price. That means they can afford to make an offer for up to $200,000 ($40k/[100%-80%]). The second buyer is working with a bank that has an investor who can take a higher level of risk and so they are willing to finance up to 95% of the purchase price. This second buyer can afford to make an offer for up to $800,000 ($40k/[100%-5%]). Sellers naturally sell to the highest bidder. Assuming there is enough demand, the maximum price is limited to the amount of capital available to the consumer. If you’re considering your options, and everyone is buyer 1, then your sale price can only be $200,000. If your market has buyer number 2, you’ll naturally try to sell to them for $800,000… just because you can.

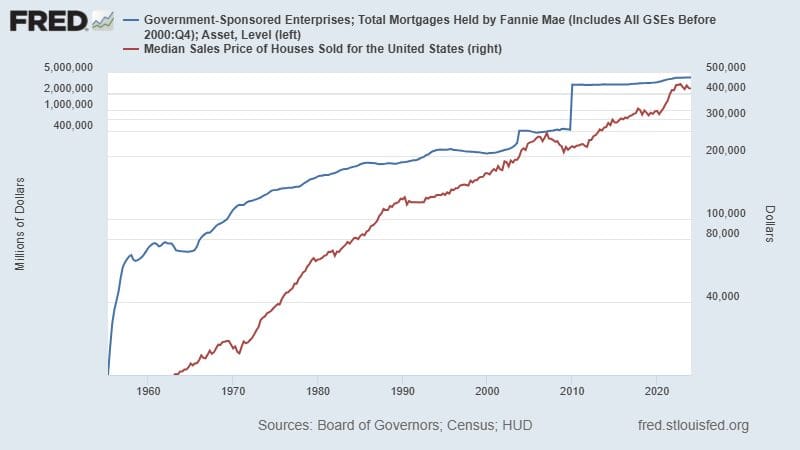

This is exactly the scenario that led to the 2008 housing crisis. Before the Government Sponsored Enterprises (Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, et al) began packaging loans and reselling them (CMOs) in the early 90s, the banks lent money from their own portfolios. This meant that they had to be more careful because they were responsible for the loan until it was completely paid off. Banks typically required 20% down because it meant that their borrower had demonstrated capacity to make payments and manage their funds for an extended period of time. Now, this may seem exclusionary to many, but changing this percentage doesn’t change how much a person can/needs to put down.

When CMOs came along, the banks no longer needed to lend from their own portfolios but could be paid to originate the loan and sell it to a third-party investor through the Government (not technically, but the GSEs are essentially the government). There was so much demand from the GSEs to buy the loan that banks could hardly justify making loans the old way, and so the GSEs gained control over the markets. To increase homeownership levels, they began lowering down payment requirements all the way down to 3% and a borrower could use up to 45% of their income to purchase. Now, if you’re the lender, and you don’t offer the 3% down option when all the other banks do, you simply lose the revenue from making the loan. Banks, who had figured out how to structure loans that were safe for both lender and consumer, could no longer compete if they didn’t conform to the GSE’s structures. This created buyer number two (along with all the other ethical problems of consumer fraud and predatory lending). Remember, you’ll sell for the highest price just because you can. Buyer number 2 had 4 times as much capital, so the home price quadruples to match the money supply.

There have been several points in history when the Government has infused a substantial amount of capital into the housing and education markets. The effect has been dramatically increased costs.

Sallie Mae is the GSE for student loans. The same principle applies to student loans as housing. If students have limited funds for their education, the universities will work within those constraints and charge less. When student loans are nearly unlimited universities would be stupid not to maximize their income. In fact, they are forced to increase student costs in order to stay competitive. If a bank were to lend to students from their own portfolio, they would want to make sure the student can pay the loan in the future. The bank would consider the cost of the education program, the income potential for the student upon graduation, and the students commitment to graduating with a degree. All three are major problems that have presented in the current crisis.

These are the fundamental economic roots of the housing affordability crisis and the student loan crisis. We could make significant headway in both areas and dramatically reduce inflation more broadly if we placed significant limits upon the GSEs or dissolved them entirely. Additionally, Student loan forgiveness would be much more palatable if there were a long-term solution to the problem. Sallie Mae could be dismantled and unwound in conjunction with some sort of student loan forgiveness program or benefit for those who have been victims of this Government Sponsored Entity.

3. Reevaluate the non-profit tax structure

Recently the Tax Foundation published a lengthy research report (available here) discussing reform of the non-profit sector, noting that the net income from business-like sources would raise nearly $40 billion in tax revenues. I’ve been very involved in charitable work and was quite perturbed at the idea until giving it full consideration.

Most of the not-for-profit sector are made up of organizations like credit unions, insurance companies, athletic associations (i.e. NCAA), consulting firms, insurance companies, and golf clubs. Most businesses can adopt the form of a non-profit organization, it just means identifying how it serves the public/its members and it can’t pay its profits to owners (it can, however just convert the dividend to “reasonable salary”). What if we narrowed the definition of what a charity is, and the non-profit businesses could pay tax on their net profits just like any other corporation would (excluding income from charitable donations). This would level the playing field for competition and broaden the tax base by approximately 10% of GDP. IF the non-profit business uses its revenues to cover its expenses, those would not be taxed just like businesses deduct their expenses. The Government could use the $40 Billion of excess revenue to help resolve its budget deficit and pay down the insane amount of debt it has amassed in recent years.

4. Remove penalties for maintaining employment into retirement age

People have been discussing the future solvency of the Social Security programs for a long time now. We have our thoughts and positions (essentially that no politician wants to alienate their voter base over an issue that won’t be critical until they have retired themselves), but have a couple of obvious observations. When Social Security was created, the average lifespan of someone taking benefits was around 3 years. It's much longer now, and we need people to retire later. Congress is obviously divided on this issue and whether we should or how we go about forcing it. At the same time, there are policies in place that disincentivize people who want to continue working. Instead of forcing a new retirement age, Congress could begin by simply removing the disincentives for staying employed and push some of their costs back into the private sector (which would in turn create more taxable profits).

The first change to address would be the social security benefit itself. Your Social Security based on your benefit at your FRA (full retirement age). For most people going forward, that is 67. If you take it early, you receive reduced benefits. If you wait to take it until age 70, you receive an 8% annual increase to your benefit over those three years. After you're age 70, there is no reason by which you could justify waiting longer. Why couldn’t we create some mechanism by which someone could continue to benefit from deferring past age 70?

Amplifying the effect, if you continue to work after you start drawing Social Security, after certain thresholds, your benefits are both partially taxable and are reduced relative to your earnings. If your goal is to continue to work into your 70’s or 80’s (more common than you would expect), then your decision causes you to lose much of your social security benefit while still paying into the system for others. The system causes a meaningful imbalance for those that could be reducing the burden on the system. We should simplify the system by increasing the ability to defer indefinitely with some incentive, and remove the benefit penalties for earned income.

The second issue to resolve is to establish a system for individuals to continue without Medicare beyond age 65. If you don’t file form Medicare at 65, you incur substantial penalties when you do file. There are exceptions to this if you properly apply, but these should be the rule of thumb. If you have adequate health coverage by another means, the Medicare program should be glad not to have to pay for your health coverage. With the broad scope of the Medicare program, this shouldn’t impact their ability to underwrite their costs. There is even a possibility it could cause a net reduction in the cost of healthcare across the board. Medicare also has significant premium penalties for those who pass certain income thresholds. If the end goal is to have more employed people contributing, this penalty needs to exclude earned income.

5. Equalize Deferral Limits and Tax Features for Retirement Savings Vehicles.

Changes to 1031 for rental properties

The current tax code allows for a property owner to sell their property in a like kind exchange. For many, they have been able to save for retirement by owning rental properties. While there is a lot of power in the ability to use debt to finance a rental or two, the structure is often less ideal when transitioning into retirement. Income is not truly passive, it isn’t from diversified sources and liquidity is a major obstacle if there aren’t significant savings in other categories. Many who have built their nest egg on a few rental properties feel trapped because of the massive tax burden they can become subject to in a sale (up to 100% of the price could be taxable). The IRS should allow, at least for a time, owners of these properties to defer taxes by depositing the proceeds into an IRA or 401(k). This allowance would allow owners flexibility to position themselves most efficiently, increase the housing supply for entry-level buyers, and would cause a net increase in tax revenue for the IRS over the long term (ordinary income vs capital gains / inherited IRA rules vs step up in basis).

Equalize contribution limits for retirement savings options

If you don’t have a retirement plan from your employer, it is much harder to save in tax deferred accounts. Your annual contributions to your IRA and Roth are limited to $7,000. IF you have a plan through your workplace, you can defer much more (23000 in a 401(k)). There are other options between and some that allow for even more. It would make sense to increase the limits of each plan to the 401(k) limits creating a fair structure for individuals and small businesses. If many people increase their contributions accordingly, it would slow the pace of inflation by removing those dollars from circulation until the account holder begins their retirement. Coming full circle, the amount of money available directly correlates to the price of goods and services. Creative solutions that remove this capital from the playing field, even temporarily, are more effective than parlor tricks with interest rates.